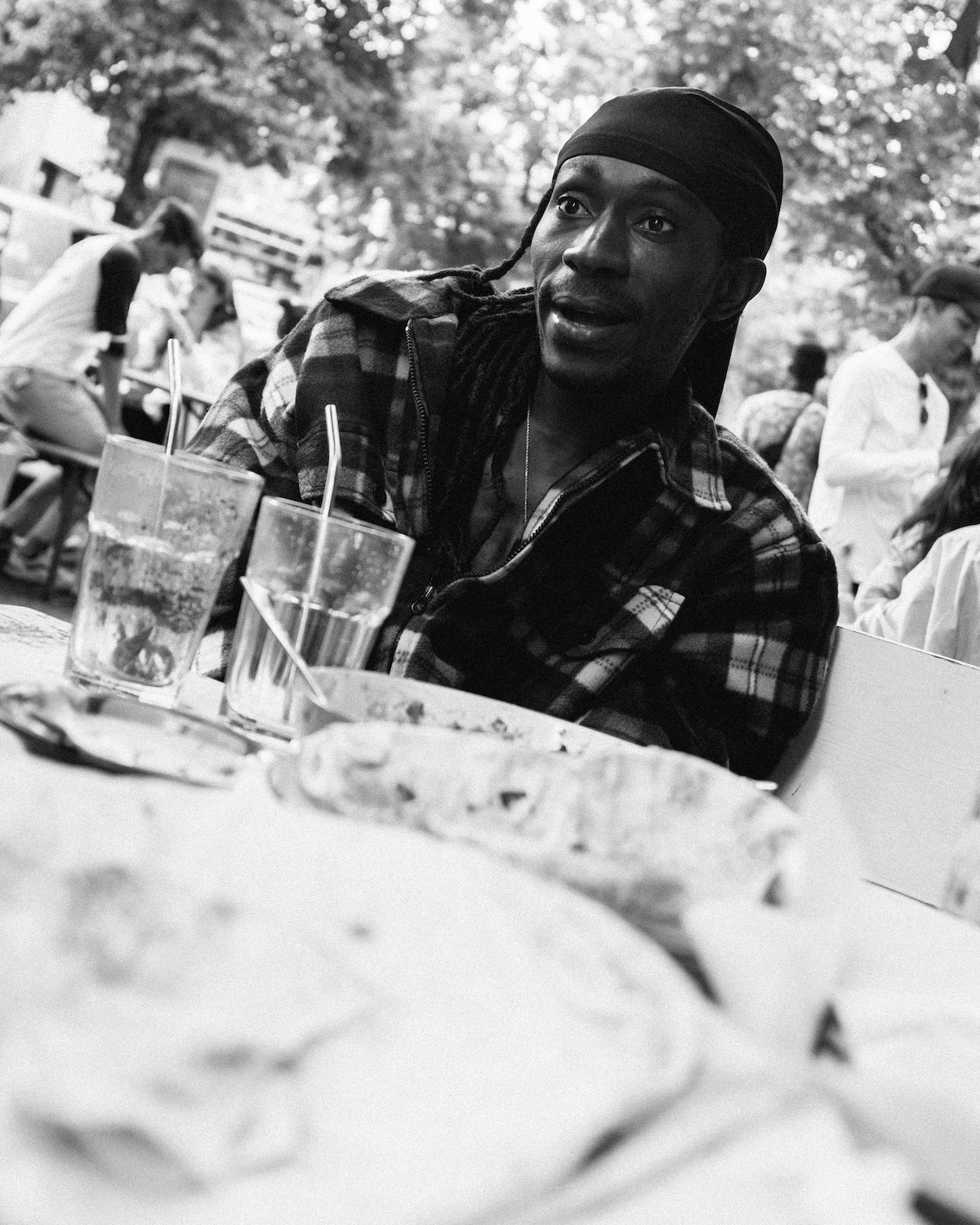

True to BSTN’s proprietary ‘Feed Fam, Fuck Fame!‘ philosophy, we’re introducing you to some members of the immediate as well as the extended BSTN family. In their own words, they talk about themselves, their career, and selected topics close to their heart. This is Feed Fam – Episode V featuring recording artist Hugo Kafumbi.

On how growing up in multiple cultures influenced his career as an artist:

It influenced my music in a very positive way, because one thing I did learn is that music is like food and you need to put different spices in the food for it to actually be tasteful and juicy. You can’t put just salt … then it will be boring. So me being in different cultures, whether it’s in Africa, Europe, or America is nothing but spices that I’m adding to my music. And so, when I’m recording it and releasing, it is very tasty

On what he has learned on his travels about the way music is consumed:

I’m still learning, traveling to different cities and different countries – music is consumed very differently. For example, in the Czech Republic, fans still want to buy CDs. I don’t press CDs anymore because nobody buys CDs anywhere else, but over there they still do. In Congo, they don’t use Spotify, they don’t use Apple Music, so they want more live shows to see you and touch you. And in Europe, everybody is on Spotify streaming. So as an artist, you have to then try to cater to everybody. Maybe It’s 200 CDs in one place while you simultaneously have to make sure your music is on Spotify because people will get really mad if it’s not. And in Africa, you need to be present. People need to touch you. They need to see you. And that’s what really I learned from traveling around places that everybody’s different. Some countries and some cities have more money, some people have no money, so it varies depending on the country or the city.

On catering to multiple audiences on different continents:

Actually, my large fan base from Africa just started, because I just started singing in my native language, which is Swahili. And that happened through the lockdown. When the lockdown happened, I couldn’t do any more shows in Prague in Czech Republic. People wanted to save money, so nobody was actually really streaming. Most people canceled their Spotify plans, so I saw the numbers drop.

When couldn’t do shows, I was very depressed, actually, with music. I thought ‘My God, what am I going to do now?’ Then I decided to switch the language and say, well, I’m going to sing to my native people because they don’t even use Spotify anyways, so maybe then I will have a different avenue of selling my music. And when I switched the language, it just blew up. It just caught fire instantly. And I was actually watching my Instagram for the longest time. The most interaction was in Czech Republic because that’s where I grew up. And within three weeks of me switching the language, boom, Congo’s number one – the most following the most interaction. And yeah, so it really came about naturally.

I didn’t have any strategy behind it about having a bigger fan base in Africa. They gravitated to my music, which is what I always wanted. In Europe, I always had to promote my music and get it to the people and place myself here. But in Africa, in Congo, I didn’t have to do anything. I just released it and it caught fire.

On his upbringing:

I was born in Congo and then when I was 13, I was adopted to go to the Czech Republic and study there. After a few years, I went to Canada and then now I’m in Berlin. When I got to the Czech Republic at 13 years old, it wasn’t so common that African people are walking around. It was extremely racist, extremely hard for me to just go outside.

I had never experienced racism before. In Congo, I was already in my home, so I didn’t even know it exists. But the beauty of it all is the music, because once I started making music, I started to influence a lot of young kids. In the Czech Republic, there are not many African or “Black” artists. You can count them on your hand. There is one of them, who’s the biggest artist in Czech and Slovak, Ben Christopher. He was born in Czech Republic, but he’s from an African descent. And the second one is me.

Our role in Eastern Europe is very important because young kids learn to understand that it’s okay to mix races. They like my music. They like how I dress. I interact with them. So we as artists are actually changing the narrative of this old school mindset.

On what’s next:

The next plan is to go back to Africa. As I said, they consume music differently. They want to see me, they want to touch me. I want to release more songs before I go over there though, so when I do, I can give them a real show.

Like I said, life and music is like food. So I think the photographers, the DJs, they need to get some spices from Congo and add them to their food because it’ll only help them grow. And in return, it’ll help Congo as well grow because you bring your spice. So, everybody has to share this culture and not be scared. Part of my goal is to bring as many artists back to Congo, make concerts for them and really build the bridge between Europe, US and Africa.

On his motivation for switching rap languages:

When I switched the language from English to Swahili and I stopped rapping in either Czech or English, I wasn’t sure if I would actually have fans. I was wondering if people thought I had forgotten my native language. They’re like: ‘He went to Europe and he forgot everything.’ I wasn’t sure if they would actually like the music, so I started posting snippets of 20 seconds on my Facebook and on my Instagram. And then, all of a sudden, I just saw people saving it on Instagram. This was crazy.

The next thing I know, my mom’s calling me like: ‘What’s going on? Did you release new music?’ I said: ‘No, I just put some snippet out to check the temperature if people will actually like it.’ And the club, the DJs, the radio stations, the taxi driver … everybody is playing these 20 seconds in the club, in the car, in the taxi, at the coffee shop. And they keep calling me. ‘When is the song out? When is the song out?’ So it’s a blessing, it really is.

Having worked in the music industry for ten years, getting this kind of reaction where people are hungry for my music … I don’t have to promote my music, it’s promoting itself. It’s a dream come true to be in this position.

On juggling being independent as an artist with the exposure that comes from bigger labels:

I never started making music for exposure. I started making music as a therapeutic treatment for myself. You know, I was adopted. Then I was kicked out. Then I was homeless. Then I was in the streets. All these things were piled up in my head, so I wanted to do something that I really love. I didn’t like school. I hated school. When I got older, I asked myself, what do you love? What do you want to put your heart and soul in?

And it was music, so I started doing it. I didn’t get any clicks. I didn’t get any views, but I kept doing it. I kept spending money in that. Most artists want to be famous. I don’t mind it, but I’m not searching for it or seeking it. So this is very easy for me to balance. I’d like to be with a label so that more people can hear my music because I feel like me, myself, a one man team, I can’t put the music where it needs to be every time.

Labels are cool, but they offer money and fame, and for me, it’s not enough, it’s not impressive. I want them to be in involved in a project that I want to do for Congo, help orphan kids. There’s a lot of projects that I’m more interested in to do for other people than for myself, so if a label is not ready to look at me as an artist and as a spokesperson for those who have less I don’t want to be with them because I’m not a product that’s for sale. I’m actually an individual who has a lot of goals to help others.

On putting people in boxes:

People look at you and they say: ‘How can we sell this guy?’ I’m not for sale. We can do business together. We can do projects together, but I’m not for sale. Whatever I feel in my heart is what I make, music-wise. Today, it can be drill, tomorrow’s R and B and the day after that it’s Afro beat, it just depends on the feeling that I’m getting. And often, labels don’t know how to work with an artist who can do everything. They want you to do one thing so they can easily sell you and make money.

On maintaining control over your creative work:

Control It is the most important thing, because for the longest time, Africans have been controlled. If I fall into the trap of being controlled, making music I don’t like, then I didn’t do my job because the ancestors already were controlled. Now, I’m in a position where I can change that. So, I will never give up the control because people died trying to fight for freedom.

It’s a statement. It’s not even important for me so I will be rich and my kids will eat from my music later. No, it’s just a statement that when people fight for you, maybe they didn’t finish the fight, you have to continue the fight. And if you don’t continue the fight, then you are a sell-out. You are useless, you know?